By Syd

By Syd

It was the best of times; it was the worst of times… No, wait — wrong story. I bought a Smith & Wesson Model 60-15 for a practice gun. This is their 3 barrel .357 Magnum version of the Model 60 in stainless steel. Its a nice gun, with a full-length grip and adjustable sights. Not being content to leave a pretty good gun alone, I decided to install a Wolff reduced power spring kit in it. The reduced power kit includes two springs: the rebound spring and the hammer spring.

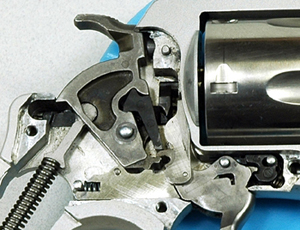

Why do this? The springs in a handgun force the various parts against each other, insuring a firm and positive engagement of the critical elements of the action: trigger, sear, and hammer. Without adequate pressure, these parts may not function properly and the gun may even become dangerous or malfunction. On the other hand, the manufacturer will always err on the side of caution and build too much pressure into the action for liability and reliability reasons. This inevitably results in a rough and heavy trigger. So, a judicious reduction of spring pressure can improve the trigger without compromising function. There are two ways to improve the trigger in any handgun: polish the action interfaces and reduce spring pressure. But if you do too much of either, the gun will become dangerous and unreliable. This is why smart people take their guns to someone who knows what they are doing to get their triggers smoothed and lightened.

Smith & Wesson revolvers have something called a rebound slide which is powered by a spring. The function of the rebound slide is to push the trigger back into the ready position after the trigger is pulled. It resets the action for the next shot. The energy for this operation is provided by a strong spring which resides inside of the rebound slide. The rebound slide sits in a channel in the frame just behind the trigger. It is held in place by a post which extends from the side of the frame. Getting this little demon from hell in and out is the worst part about working on a Smith & Wesson revolver. Brownells makes a tool which helps somewhat in getting the rebound spring back in, but its still a PITA.

One resource I consider indispensable to this operation is Kuhnhausens S&W Revolver, A Shop Manual. In fact, I will state this in terms of an imperative: Do not attempt this operation without the Kuhnhausen manual. Kuhnhausen walks you through the disassembly process and the elements of lightening a trigger.

Once inside the Model 60, I did some polishing on the sear interfaces and the area where the rebound slide moves inside the frame and makes contact with the trigger. I polished the rebound slide itself. I am a very gentle polisher. I use red jewelers rouge and a variable power Dremel with a felt polishing bit. I also have a couple of Arkansas white whetstones that I use for smoothing and rounding over edges. I almost never grind or cut metal, especially on sears. Many of the action parts in guns these days are Metal Injection Molded (MIM). Their surfaces are hard, but they are thin. The metal inside MIM parts is somewhat softer, and if you grind through the hard surface into the soft interior metal you will ruin the part and leave it non-functional. Grinding or cutting may also change the sear interface angles and this can result in a dangerous and/or unreliable gun. Anything more than a gentle polish and lubrication of these interfaces should only be done by a certified gunsmith. I polished and lubed with Mil-Comm and put the gun back together. I was very pleased with the results. The trigger is a little bit lighter but not a whole lot, but it is very smooth.

Following my stunning success with changing out the spring set in the Model 60, I decided that I’d take on the Airweight. Should be all the same, right? Wrong. I took it all apart, cleaned out eight years worth of crud, polished and lubed. I installed the same springs I used in the Model 60 the 8 lb. hammer spring and the 14 lb. rebound spring. No matter what I did, the rebound slide wouldn’t work right with the Wolff spring in it. It would buck up in the front instead of moving straight back when the trigger was pulled. I took the thing in and out so many times that my thumb got raw from putting the rebound spring back in. Then to make matters worse, I pulled the cylinder hand off of the trigger, not realizing that there was a little spring hidden in the body of the trigger. Of course, when I put it back together, it didn’t work right. Research project. Oh, there’s a little spring somewhere. Miracle of miracles, I managed to find the spring among the dust bunnies and I had no idea of how it went back in. Spent some time searching the Smith & Wesson forum and found some instructions for how to get the little child of Satan back in. (Its also in the Kuhnhausen manual, but I didnt know that at the time.) Getting the spring back in wasn’t too terribly hard. The rebound slide bucking was another thing, however. Nothing I did would make it work. I finally put the stock rebound spring back in and everything was Jake.

Following my stunning success with changing out the spring set in the Model 60, I decided that I’d take on the Airweight. Should be all the same, right? Wrong. I took it all apart, cleaned out eight years worth of crud, polished and lubed. I installed the same springs I used in the Model 60 the 8 lb. hammer spring and the 14 lb. rebound spring. No matter what I did, the rebound slide wouldn’t work right with the Wolff spring in it. It would buck up in the front instead of moving straight back when the trigger was pulled. I took the thing in and out so many times that my thumb got raw from putting the rebound spring back in. Then to make matters worse, I pulled the cylinder hand off of the trigger, not realizing that there was a little spring hidden in the body of the trigger. Of course, when I put it back together, it didn’t work right. Research project. Oh, there’s a little spring somewhere. Miracle of miracles, I managed to find the spring among the dust bunnies and I had no idea of how it went back in. Spent some time searching the Smith & Wesson forum and found some instructions for how to get the little child of Satan back in. (Its also in the Kuhnhausen manual, but I didnt know that at the time.) Getting the spring back in wasn’t too terribly hard. The rebound slide bucking was another thing, however. Nothing I did would make it work. I finally put the stock rebound spring back in and everything was Jake.

It’s fairly smooth now (although it was pretty good before), but it left me with the impression that not all j-frames are created equal. I cant say Im completely happy with the job on the Airweight. It also left me with the realization of how delicately tuned and balanced the components of revolvers are, and changing springs and such in and out of them is more perilous than analogous operations on bottom feeders.

The last thing that needs to be said about this relatively simple operation is that it’s a far cry from a full action job that you would get from one of the revolver action masters like Teddy Jacobson. A full action job would include truing up the sear faces, adjusting the let-out of the double action sear, checking the cylinder yoke for straightness, eliminating end shake in the cylinder, and other elegant pieces of voodoo that only those guys know. Such things are way beyond the scope of this article, at least for now. Just be aware that there is much more to a full action job in a revolver than just switching out the springs. In some respects, the action of the revolver is far more complex and esoteric than a semi-auto action. The interaction of the parts is delicately balanced, not unlike a watch, and the inner workings of the lockwork are less intuitive to understand, requiring serious study to master. A simple “keep you out of trouble” rule would be, “If you don’t know the answer, don’t do the operation.”

Comments, suggestions, contributions? Contact me here