By John Taffin

By John Taffin

Bellygun is a term you don’t hear much any more, but from the time of the Civil War up to very recently, that’s what short-barreled revolvers were called. Some people in the gun business tried to gloss over the genre of small, concealable handguns, but the snubnosed bellygun is the most important type of all firearms because it is made for self-defense.

Bellyguns were first offered in the seven-shot single-action .22 rimfire by Smith & Wesson in the 1850s. It was favored as a hideout weapon on both sides of the Civil War. In the first half of the 20th century, every little store had a punchboard with one of the main prizes being a nickel-plated pocket pistol. No forms to fill out, no instant check, no waiting period. You hit the board, you won a gun.

Even in my family, which was certainly not part of the gun culture, I found such a little pocket pistol, an Iver Johnson, among my grandfather’s effects after his death. Today the media has picked up on what was originally a racist term of derision, Saturday Night Special. There are no such guns. Saturday Night Specials are certain people with a certain mindset, not an inanimate object such as a life-savin’ bellygun.

Smith & Wesson’s first double-action bellygun was the break-top of 1880, chambered in .38 S&W. In 1882, S&W brought forth the “lemon-squeezer,” a hammerless double-action with a grip safety. These guns featured not only a grip safety, but also an extra heavy DA-only trigger pull to make it that much more difficult for a child to operate. These guns were very popular as pocket pistols since there was no hammer to catch in the clothing.

I lucked onto one of these in excellent shape in a strange way. My daughter moved into an old house and, while she was cleaning it, she noticed a loose board in the back of a closet. She pulled it out and found a 1 lb. candy tin. Inside she discovered a 1935 championship high school ring, a box of .32 S&W and a .32 lemon squeezer. The rubber grips are perfect, while the rest of the gun is 98 percent with very minor nickel flaking. It works just as well today as it did more than 100 years ago when it left the Springfield factory.

In the 1890s Smith brought forth their first solid frame, swing-out cylinder gun, the I-frame. The little gun was beginning to take on the profile that is so recognizable today. These little I-frames were chambered in .32 S&W, .38 S&W and, in 1911, thanks to a gun dealer by the name of Bekeart, in .22 rimfire. The .22 would evolve into that grandest of all little sixguns, the .22/32 Kit Gun in 1936.

The late Col. Rex Applegate was often involved in clandestine operations from his early days with an outfit known as the OSS in World War II through his commissioning as a general in the Mexican Army. One of his favorite pocket pistols was the .38 S&W. At least until he found himself emptying it to stop an attacker.

More power was needed in pocket pistols. Colt had chopped the barrel of their Police Positive to 2″ before World War II and called it the Detective Special. It was a start in the right direction, but with its six-shot cylinder, it was a mite big for a pocket pistol.

The answer was soon forthcoming. Smith & Wesson engineers had been working to improve the I-frame by slightly enlarging it to take five rounds of .38 Special. In addition to a larger frame, the new revolver, dubbed the J-frame, used a coil mainspring. It was very much like the .38 S&W I-frame except for the extra long cylinder, filling the J-frame window.

To introduce the new pocket pistol, the J-frame was taken to the 1950 annual meeting of the conference of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, You are probably now ahead of me and can see the name coming. The police chiefs voted on a new name and the first I-frame was appropriately given the name of .38 Chief’s Special.

It is altogether fitting that the police chiefs should knight the new five-gun, as it became immensely popular with peace officers as a second or backup gun that slipped easily into a uniform pocket or as a very easily concealed and carried off-duty weapon. For 40 years, until the revolution of sorts in semiautomatic weapons, it was the pocket pistol by which all others were judged.

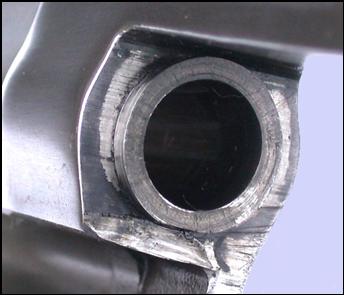

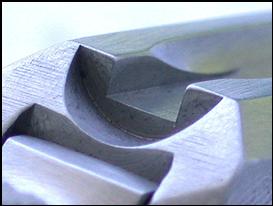

Not only was the J-frame .38 Chief’s Special a near perfect pocket gun, but also it was extremely strong. The bolt cuts came between the cylinder chambers and the cylinder itself to fill the frame, with no unsupported portion of the barrel sticking back through the main frame as found on the .357 Magnum and .44 Special Smith & Wessons of the time.

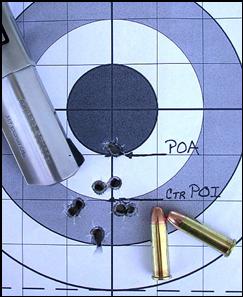

How strong are these little pocket revolvers? Elmer Keith reported in 1955 that both of them would perfectly handle the .38/44 and other high speed .38 Special ammunition, as he ran 500 rounds through a Chief’s Special with no ill effects. At the time of Keith’s writing the .38/44 was a +P loading, the forerunner of the .357 Magnum, rated at 1,150 fps from a 5″ Smith & Wesson .38 Heavy Duty sixgun.

I’ve gone even further with my little Chief’s Special. In the pre-.357 Magnum days of the early 1930s, Keith came up with a heavy .38 Special loading for his sixguns that does 1,400+ fps from an 8 3/8″ S&W .357 Magnum. Using this load in a Chief’s Special, the recoil is stout, with a muzzle velocity of 1,150 fps with a 168 gr. bullet from a 2″ barrel. This is not something I recommend and I do not shoot loads like those very often, but it is great to know that option is mine should I need it.

The .38 Special Chief’s became the Model 36 in 1957, the Centennial became the Model 40, while the number 37 was attached to the Airweight Chief’s Special. In 1965, a revolution of sorts arrived in handgun manufacturing when Smith used the Model 36 as the platform for the same gun in stainless steel. This of course is the Model 60.

A favorite little sixgun of hikers, backpackers and fishermen is the six-shot .22 Kit Gun on the J-frame platform. The Model 34 with either a 2′ or 4′ barrel was produced from 1953 to 1991. It then became a stainless steel sixgun, the Model 63, and was subsequently joined by the Model 651, the .22 Magnum version, and the very rare (only offered in 1990) .32 Magnum Kit Gun, the Model 631.

These diminutive sixguns make fine companion guns for the hunter who does not want to pack any more weight than necessary, but can still be prepared to take a grouse, squirrel or rabbit for the camp cooking pot.

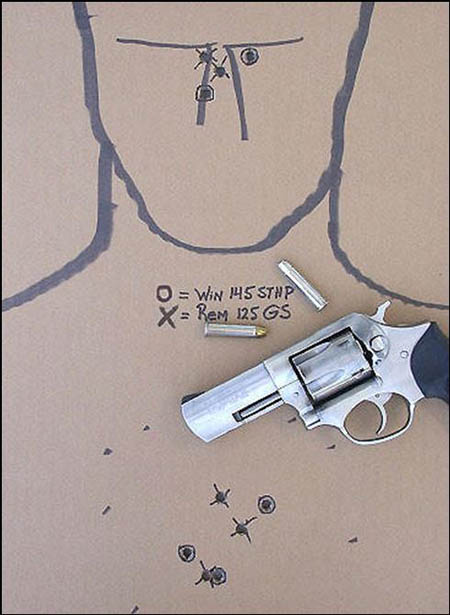

The 1990s brought major changes in the J-frame series. All of the older .38 Specials are gone. Today’s J-frame is slightly larger with a 2 1/8″ barrel and chambered in .357 Magnum. In the mid-1930s, a heavy duty, large framed .357 Magnum was looked upon as the ultimate sixgun. Now we have the .357 Magnum chambered in a 24 oz. five-shot pocket pistol. Firing full house 158 gr. .357 Magnums in one of thee little J-frames is a real attention getter. On both ends.

My wife carries Smith & Wesson J-frames. In her fanny pack is a blued Airweight with a 2″ barrel while her purse gun is a 3″ stainless steel Airweight. Both of these are the Bodyguard models with no hammers exposed. From blued to airweight to stainless to titanium, the J-frames keep evolving. Loaded with 125 gr. JHP, I can think of no better carry gun for wife, mother or daughter than these.

By Stephen A. Camp

By Stephen A. Camp

By Dan Smith –

By Dan Smith –  Design Notes –

Design Notes –