Smith & Wesson Models 40, 42, 640, 940, 442, 642, 340Sc, 342Ti and 340PD

Smith & Wesson Models 40, 42, 640, 940, 442, 642, 340Sc, 342Ti and 340PD

The Smith & Wesson Model 640 Centennial is easily the most recommended variant of the J-frame line if the Internet counts for anything in gun selection. In 2006, the best selling firearm offered by Smith & Wesson was the Model 642, the Airweight version of the 640. It is often called hammerless which is a misnomer of sorts because it actually does have a hammer; its just completely enclosed within the frame, making the revolver double action only (DAO). It is a smooth, snag-free design which makes it ideal for pocket carry. Jim Supica, author of The Standard Catalog of Smith & Wesson, said of the 642 that it was possibly the finest pocket revolver ever made.

One might jump to the conclusion that the hammerless design is a new thing brought about by our litigious society, but in fact, the hammerless design is quite old. Smith and Wesson introduced the Safety Hammerless .38 S&W in 1887. This gun was often called The Lemon Squeezer because it had a grip safety on the back strap. One had to squeeze the grip in order to fire the gun. In 1888 they produced a few of the .32 S&W Safety Hammerless pistols with 2 barrels. It was nicknamed the Bicycle Gun and may be S&Ws first production snubnose, but the Bicycle Gun is very rare. The Safety Hammerless pistols were top-break designs.

In 1952, Smith & Wesson applied the concept of the Safety Hammerless to the J-frame Chiefs Special and got the Centennial. The gun was named in honor of the company’s 100th birthday. In 1957, when the switch was made from named models to numbered models, the Centennial became the Model 40. Also in 1952, an Airweight Centennial was introduced which became the Model 42. Some 37 specimens of the Model 42 were built with aluminum alloy cylinders, but the rest had steel cylinders. These two models were produced from 1952 to 1974.

In 1990, the Centennial was re-introduced but in stainless steel and without the grip safety as the Model 640. It was a .38 Special. In 1996 the 640-1 in .357 Magnum was offered. Airweight versions, Models 442 (blued) and 642 (stainless) were also brought to market. As noted earlier, the Model 642 has been enormously successful.

As the centuries changed, Smith & Wesson worked in exotic space-age metals such as titanium and scandium to make the guns even lighter, and yet strong enough to chamber the .357 Magnum cartridge. While it still eludes me why anyone would want to fire .357 in an 11 ounce gun, I guess some folks do it. The new metallurgy produced models such as the 340Sc, the 342Ti and the 340PD.

Between 1991 and 1998, S&W produced the Model 940, a stainless Centennial chambered in 9mm. A group of three hundred were built in the .356 TSW caliber (good luck finding ammo for that one), and a prototype Model 942 Airweight in 9mm was built but did not go into production.

The design is a winner. One of the J-frames greatest assets, its ease of carry, is further enhanced by the snag-free concealed hammer design. But do you lose anything by going to the double-action-only format?

DAO versus DA/SA

Ill admit to a preference for exposed hammer revolvers. I don’t know why really. Maybe its the traditionalist in me. Maybe its because I like to have the option to fire single action if I want to. Single action fire is generally thought to be more accurate than double action. When target shooting and hunting, people prefer to manually cock the hammer to get that wonderful crisp 1 lb. trigger that a good revolver firing single action can give you. The sights just move around less when you don’t have to apply the force needed to cock the hammer.

On the other hand, people who carry a revolver for self defense should practice almost exclusively for double action fire, as if the single action option wasn’t even there. Why? Because there are almost no situations in which single action fire is appropriate in self defense. Most self defense situations unfold rapidly. There isn’t time to thumb cock a revolver and take careful aim in the way one would do while target shooting. A cocked revolver is dangerous in the adrenaline dump of a lethal force encounter. The trigger is just too light. Its too easy to fire when you don’t mean to. There was a well-publicized case in Miami several years back in which a police officer accidentally shot a suspect he was holding at gunpoint with a cocked revolver. The suspect was killed and the officer faced a lengthy court process which ultimately destroyed his career. In a nervous situation, a cocked revolver is dangerous. When you’re really nervous or scared, the heavy double action trigger pull is an asset rather than a liability. I can hear you say, Keep your finger off the trigger until you’re ready to fire, and that’s true, but we also know that people don’t always do what they’re supposed to do in the stress of a deadly encounter. The police officer in Miami is a good example. I’m sure he had heard the rules. A firm double action trigger can be a welcome piece of insurance against an accidental discharge. With the DAO Centennial, manual cocking isn’t possible, nor is it possible to be accused of negligently cocking the hammer in a civil action which could follow a self defense shooting.

Is there a case to be made for the DA/SA? A little imagination can generate scenarios in which single action fire could be an asset: a hostage situation, a survival situation in which a careful shot on a game animal might make the difference between living and starving, some kind of broken field situation in which there is an active threat but it is further away than a few yards. Admittedly, these all fall into the one-in-a-million category, but if its possible, it could happen.

As we have often seen before, all handguns are studies in compromise. For a self defense revolver, the Centennial seems to be an acceptable trade-off. Single action fire is sacrificed for superb, snag-free conceal-ability and the elimination of certain liabilities.

Reactions to the Smith & Wesson Model 640

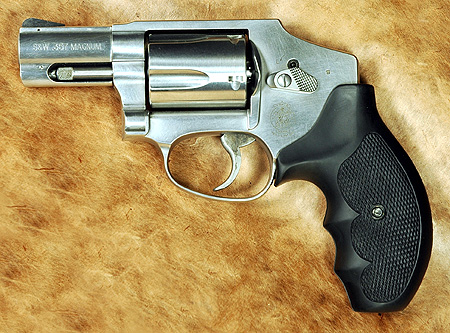

The gun pictured here is the Model 640-3. It is the stainless steel .357 Magnum version with the integral lock. It is a beefy, solid snubby that balances well in your hand. With its solid construction and 23 ounces of weight, it will handle the hottest ammo without tearing your arm off. The sights are the standard notch type that are characteristic of this class of guns. They’re not great and I don’t see them too well, but they don’t snag and this is a close-range gun. The smooth organic contours of the 640 make it a superb concealed carry gun. It’s a bit heavy for pants pocket carry. If you like the Centennial but expect to do a lot of pocket carry, I would recommend the Airweight version, the Model 642 in .38 Special +p. If you like really hot ammo and/or intend to carry mostly in holsters and fanny packs, the heavier 640 is the ticket. I’m not sure about the dynamics of it, but the all-stainless J-frames seem to have better triggers NIB than the Airweights and AirLites do. The all-stainless versions are shooters. You can do extended range sessions or even matches (if you’re brave) with these without reducing your hand to a bloody pulp. It seems that most times I have watched people shoot Airweights and Airlites, they do about 15-20 rounds and quit because it’s uncomfortable. You can do a couple hundred rounds in the stainless guns and enjoy it. They’re also more controllable for rapid strings of fire because of their weight.

While I think the Model 60-15 remains my favorite tactical J-frame for it’s superior ballistics, sights, and ejector rod, the Model 640 is an easier gun to carry and has much to commend it. It is compact, powerful, robust, snag-free, and endowed with the legendary reliability of the Model 60 family of revolvers.

Comments, suggestions, contributions? Contact me here