By John Taffin

Mention Smith & Wesson and most shooters will immediately think of one of two things, either big bore Magnum sixguns, or state-of-the-art semi-automatic pistols. As a writer I’ve spread a lot of ink discussing both of these types and as a shooter I’ve run thousands of bullets down the barrels of slick shootin’ Smith sixguns and fast-firing defensive pistols. But there are other Smith & Wessons such as the Model 41 .22 target pistol and the epitome of target guns from a few decades ago, the K-38 .38 Special and the K-22 .22 Long rifle, the famous Masterpiece revolvers.

All of these handguns are guns that I would label high exposure. They are seen at target ranges, in the hunting field, worn openly on the belt of peace officers, as well as campers, hikers, fisherman, in fact, all types of sportsmen. Chambered in .22 they are used not only for target shooting but by thousands upon thousands of families enjoying the great sport of plinking together. Larger calibers are carried for more serious purposes such as hunting and law enforcement.

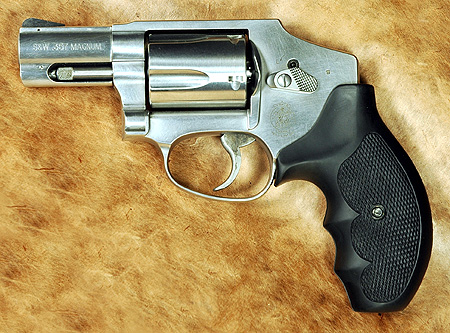

There is another whole class of Smith & Wesson handguns, a group of revolvers rarely ever seen. These are the guns carried concealed by civilians and peace officers alike. These are the guns kept in countless bedside stands, under store counters, in tackle boxes, and day packs. These lightweight easily concealable handguns are the J-frames. Smith & Wesson has long utilized the alphabet to distinguish their revolvers: the N-frames, the largest .41 and .44 Magnum, .45 Colt, .45 ACP, and even .357 Magnum; the middle-sized K-frames, the .357 “Combat Magnum” and earlier mentioned Masterpiece revolvers; the L-frame, the newest intermediate sized .357 Magnum; and finally the diminutive J-frames chambered in .38 Special, .32 Magnum, .22 Long Rifle, and .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire.

History of the J-Frame

The first small frame double action Smith & Wesson, a .38, was built in 1880. This was not the famous .38 Special which would come later, but the less powerful .38 S&W. The first .38 DA weighed 18 ounces and would go through five design changes, thirty-one years of production, and number more than one-half million examples of top-break design. These were followed by the Perfected Model .38 with a solid frame/trigger guard combination , but still of the top break design, that led the way for the solid frame, swing out cylinder revolvers to come.

At the same time that the top-break .38’s were being made, the same basic design was offered in .32 S&W caliber with nearly 300,000 of the smaller caliber being made. Shortly after production began on the .38 and .32 Smith & Wesson Double Action Models, D.B. Wesson worked with son Joseph to develop a completely different style of revolver. Lucian Cary, a well known gun writer of forty years ago relates the following legend.

“When Daniel Wesson read a newspaper story about a child who had shot himself with the family revolver, his conscience hurt. He told his wife that he would make a revolver that could be safely kept in the bureau drawer. It was his custom to receive his grandchildren every Sunday. No doubt it was tough on the grandchildren. Daniel Wesson must have been a fearsome man, with his thick body, his great beard, and his virtue (Cary obviously did not understand grandfathers and grand children and the bond between them!) But on one occasion it was his young grandchild who put it over.

The Safety Hammerless

Daniel Wesson made a revolver he thought no child could fire. He gave it to his grandson, Harold Wesson, now president of Smith & Wesson (this was in the 1950’s) and challenged him to fire it. Harold was only eight years old but he knew that his grandfather expected him to fail. Maybe that gave him a shot in the arm. Harold tugged at the trigger with all his strength and fired the gun. His grandfather went sadly back to his shop–not that day, of course, which was Sunday, but on the following Monday. Some weeks later he again presented a revolver to Harold and asked him to pull the trigger. Harold did his best. But he failed.

The gun the boy couldn’t fire was the New Departure, also known as the safety hammerless. It had a bar in the back of the grip supported by a spring. You had to squeeze the grip hard enough to depress the spring and pull the double action trigger at the same time in order to fire the gun. No child of eight had the strength to do both at once. The New Departure was an uncommonly safe bureau drawer revolver.”

The Safety Hammerless, so designated by the fact that the hammer was completely enclosed by the revolver frame, became the first really practical pocket gun. Five hundred thousand of these were made in .32 and .38 caliber from 1886 until 1940.

With the advent of the I-frame Smith & Wessons in 1894, the basic design was changed from top break to a solid frame, swing-out cylinder style of revolver. Over the years from before the turn of the Century until 1960, the I-frame was offered in .32 Hand Ejector, .22/32 Hand Ejector, which became the .22 Kit Gun, .32 Regulation Police, .38 Regulation Police, and .38 Terrier.

The Chief’s Special

In 1950, one of the most famous of the Smith & Wesson revolvers arrived. A five-shot, compact revolver to fire the more powerful .38 Special instead of the .38 S&W was introduced at the Conference of the International Association of Chief’s of Police in Colorado Springs, Colorado and has been officially and lovingly known as the Chief’s Special ever since. This was the first J-frame revolver and was larger than the I-frames and chambered in .22, .32 S&W Long, and .38 S&W. In 1960, all I-frames became J-frames.

The Chief’s Special has been offered in a number of versions along the way: the standard Model 36 in both round and square butt versions, the Airweight Model 37, the Model 38 Bodyguard which had an extended frame that protected the hammer and exposed only enough of the tip to allow for cocking. The Number “39” was used for Smith’s new double action 9MM Semi-automatic in the 1950’s, but the J-frames resumed with the Model 40 Centennial, a J-frame “Safety Hammerless”.

In 1965, a most significant J-frame variation appeared. One that was to have far reaching consequences throughout the firearms industry as the Model 36 Chief’s Special was offered as the Stainless Steel Model 60. Instantly popular with peace officers and outdoorsman alike, the first stainless steel revolver revolutionized firearms and stainless steel revolvers are now a major part of the handgun industry. Stainless is so much a part of the handgun market, and especially with the small frame concealable firearms that are carried closest to the body, that of the five J-frames I have been testing, four are stainless, and the fifth has been custom finished to look like stainless.

Metalife was applied to a Smith & Wesson Chief’s Special, a two-inch Model 36 .38 Special. Depending upon the weather, it has been carried in an inside the pants holster, in an ankle holster, in a boot top, and in the pocket of insulated coveralls. This particular revolver has been further customized by sending it to Teddy Jacobsen. Jacobsen is an ex-cop now in the gun smithing business and he did one of his famous action jobs on the little Chief’s Special along with polishing the trigger smooth, de-horning the hammer spur, and also jewelling both hammer and trigger. When combined with the Metalife finish, these modifications make the Model 36 into a near-perfect pocket pistol.

The only thing left to do to finish off the round butt Chief’s Special was to fit it with custom grips. I just happened to be carrying this little gun when I visited Herrett’s. I soon had a pair of Detective stocks for the Chief’s!

The modification makes the little Chief’s into a beautiful close range double action defensive pistol and the hammer can still be cocked for a longer deliberate single action shot by starting the trigger back and catching the hammer with the thumb to finish the cocking procedure.

As a companion piece to the 20 ounce Chief’s Special, I have been testing the same basic gun, in this case a Model 60 Stainless Steel “Chief’s Special”. Friend and gun writer Terry Murbach certainly deserves at least some of the credit for suggesting the .38 Special Stainless Steel that Murbach feels should be known as “The Trail Masterpiece”. This little 23 ounce, round butted .38 sports a three inch full under-lug barrel and fully adjustable sights. The sights are exactly the way they should be, black both fore and aft. Yes, even though the newest Model 60 is stainless, the rear sight assembly is black and the front sight blade is quick draw style, plain black and pinned to the stainless steel ramp.

Anyone who has read many of my articles know that my usual forte is the big and bold, the Magnum and beyond sixguns and the big bore semi-automatics. But I have definitely found a place in my collection for this little five-shooter. A Plus P five shooter I might add as Smith & Wesson does classify this little .38 as one that is able to handle the hotter loads. No little strength certainly comes from the fact that the Model 60 carries a full length cylinder with very little barrel protruding through the frame unsupported. The cylinder also, being a five shot, has the bolt cuts between chambers rather than under them.

J-Frame Variations

When the J-frame Smith & Wessons came in, I went to the local gun shop, Shapel & Son’s, and found three dusty old boxes down behind the counter containing long-out-of-production Jay Scott Gunfighter J-frame stocks. At the present time they ride unaltered on three J-frames but all will receive extensive customizing in the future which will see the removal of the finger grooves and the checkering that adorns two pair.

The Model 60 Trail Masterpiece wears plain walnut Gunfighter grips that will clean up very nicely as time and ambition permit making the Trail Masterpiece an even more desirable little fivegun for hiking, fishing, camping, etc. And with the right loads, the three-inch barreled .38 will make a fine little close range varmint and small game gun.

I can only find one fault with the Model 60 Trail Masterpiece and that is strictly the result of my own preference for smooth triggers. All other test J-frames came through with smooth triggers but the this three-inch .38 boasts a grooved trigger that you can bet will become a smooth trigger in the future as it will be sent to Jacobsen for one of his action jobs after a check to Smith & Wesson makes it mine.

Chic Gaylord, New York leather worker and the father of the modern concealment holster, was a real fan of the three-inch .38 Special and promoted a “Metropolitan Special Adaptation” of the Colt Police Positive consisting of three-inch barrel, ramp front sight, nickel finish, bird’s head butt, grip adapter, and trigger shoe. Another favorite of his was the three-inch Chief’s Special with Fitz Gunfighter grips. He would have loved the Trail Masterpiece.

The firing tests of the Model 60 .38 Special Trail Masterpiece gave quite pleasant results. Considering the short sight radius the three-inch barrel affords, and also considering that the test groups were fired at 25 yards, and especially when one considers that the groups were fired by my hand and eye combination, some groups border on the phenomenal. The two-inch .38 Special Chief’s Special was fired double action only on combat targets and not for group size. It proved to be quite capable as a defensive revolver.

SMITH & WESSON J-FRAMES

CALIBER: .38 SPECIAL TEMPERATURE: 60 DEGREES

CHRONOGRAPH: OEHLER MODEL 35P GROUPS: 5 SHOTS @ 25 YDS.

MODEL 060 3″ HB – – – MODEL 36 2″

LOAD – MV – GROUP – MV

RCBS #35-150 /6.0 UNIQUE – 975 – 2 1/2″ – 961

LYMAN #358156GC /5.0 UNIQUE – 716 – 3″ – 691

LYMAN #358429 /5.0 UNIQUE – 758 – 1 5/8″ – 720

158 SPEER SWC /5.0 UNIQUE – 750 – 2 5/8″ – 735

BULL-X 158 SWC /5.0 UNIQUE – 782 – 3 1/2″ – 708

LYMAN #358429 /6.6 AA#5 – 890 – 3 1/8″ – 815

158 SPEER SWC /6.6 AA#5 – 830 – 3 1/2″ – 795

BULL-X 158 SWC /6.6 AA#5 – 821 – 3″ – 785

BULL-X 148 WC /6.0 AA#5 – 861 – 2 3/8″ – 841

SIERRA 110 JHP /8.8 AA#5 – 1067 – 2 3/4″ – 1017

SPEER 140 JHP /6.0 UNIQUE – 934 – 1 5/8″ – 913

CCI LAWMAN 125 JHP +P – 1019 – 2 1/2″ – 932

BLACK HILLS 125 JHP – 864 – 3 1/4″ – 792

The .32 Magnum, heretofore offered in medium framed sixguns like the Ruger Bisley and Single-Six, the Dan Wesson double action, and the Smith & Wesson heavy underlugged barrel K-Masterpiece, is a natural for the little J-frame revolvers. Unlike the five shot .38 Special J-frames, the .32 Magnum is a six-shooter. My original request for test guns from Smith & Wesson was for a .32 Magnum and a .32 S&W Long J-frame, but both guns came through as .32 Magnums. One is a “Kit Gun”, a four inch barreled, adjustable sighted, easy packin’ Kit Gun. The other is quite the opposite, a three-inch Centennial Airweight .32 Magnum. The latter is a 16 ounce concealed hammer sixgun, a very easily concealed and even more easily packed aluminum framed revolver.

The four-inch, 23 ounce Model 631 Kit Gun is meant for the woods loafer, fisherman, camper, while the totally dehorned and no-sharp-corners, double action only Model 632 is the concealment counterpart. A defensive gun designed for the shooter who wants a powerful weapon without objectionable recoil. A .32 that can be shot well is certainly much better than a poorly handled lightweight .38 Special; a gun that is easily carried is certainly better than a heavy gun that is left behind. And even at its one pound weight, the .32 Airweight handles very pleasantly and pokes nice little groups double action style at 10 yards.

The adjustable sighted four-inch .32 Magnum is a two to three -inch gun at 25 yards. Load development may help reduce these groups in the future. A load that would be capable of head shooting squirrels, rabbits, and grouse at reasonable ranges would make the little .32 into a real gem.

SMITH & WESSON J-FRAMES

CALIBER: .32 MAGNUM TEMPERATURE: 60 DEGREES

CHRONOGRAPH: OEHLER MODEL 35P GROUPS: SIX SHOTS @ 25 YDS.

MODEL 631 4″ – – – MODEL 632 3″

LOAD – MV – GROUP – MV

FEDERAL 95 LEAD – 941 – 2 5/8″ – 895

FEDERAL 85 JHP – 1020 – 2 1/2″ – 954

NEI 100.313 /8.3 #2400 – 1131 – 2 3/8″ – 1043

NEI 100.313 /5.5 AA#5 – 1122 – 2 3/8″ – 1027

HORNADY 85 XTP /8.3 #2400 – 1044 – 3″ – 942

HORNADY 85 XTP /5.5 AA#5 – 1074 – 2 3/8″ – 924

SIERRA 90 JHP /8.3 #2400 – 1100 – 3″ – 952

SIERRA 90 JHP /5.5 AA#5 – 1070 – 2 7/8″ – 885

The final J-frame tested is one of Elmer Keith’s favorite guns resurrected for 1991. Elmer is best known for his work with the .44 Special from 1927 to 1955 and the .44 Magnum thereafter. But Elmer also used other guns and one of his favorites was the Smith & Wesson Kit Gun chambered for the .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire.

J-Frames and Handgun Hunting

Elmer writing in 1961 in the second edition of his famous book SIXGUNS BY KEITH had this to say about the .22 Kit Gun: “Last winter Jack Nancolas, our local Government hunter killed three treed cougar and ten bobcats with my K model S.& W. .22 rim fire magnum and this winter he killed fifteen bob cats and two cougar with my 3 1/2″ barrel S.& W. kit gun for the same .22 R.F. Magnum load. The last cougar, a big one, jumped out over Jack’s head as he approached the tree in the hope of a brain shot. As it was getting late and he had trailed the big cat all day, he simply took a fast double action snap shot at the brute as he sailed over his head. The tiny soft-point slug hit the big cat square in the chest, penetrating his heart and thence the spine; and he folded up in the air like a duck stricken by a dose of no. 6 shot. His head sagged on his chest and his tail carried nearly vertical, he dropped to the horizontal and rolled into a ball before he ever hit the ground. Jack ran down the mountain and poured two more into his skull to be sure he would not hurt the dogs but he was already dead and they were not needed.”

The latest edition of the .22 WMR Kit Gun, the Model 651-1 is a four-inch, adjustable sighted, stainless steel, square butted, 26 ounce .22 sixgun. The rear sight is fully adjustable and plain black, very good, but the front sight is stainless steel with a red insert, not so good for my eyes in bright light. The front sight is also much too tall for my eyes and shooting style requiring the rear sight to be raised clear out of its mortise to sight the Kit Gun in at 25 yards. Since this .22 WMR is a keeper, the front sight will be replaced with a plain black post that will be filed to the right height to allow it to be sighted in at 25 yards with the rear sight all the way down.

While the Model 651-1 is a sixgun, it works much better as a five gun with five chambers able to put five shots in less that one inch at 25 yards. I will carry it fully loaded with six shots but with the best five coming up first. Probably the most practical of all the J-frames for the outdoorsman, with the right load and chamber selection, this little .22 is definitely capable of head shooting small game and varmints, and even putting the coup-de-grace on downed big game.

SMITH & WESSON MODEL 651

CALIBER: .22WMR BARREL LENGTH: 4″

CHRONOGRAPH: OEHLER MODEL 35P TEMPERATURE: 60 DEGREES

LOAD – MV – 6 SHOTS/25 YDS.

CCI .22 MAXI-MAG – 1335 – 2″

CCI MAXI-MAG HP – 1355 – 2 1/8″

CCI MAXI-MAG +V – 1608 – 2 3/8″

FEDERAL FMJ – 1240 – 3 1/4″

FEDERAL JHP – 1046 – 1 5/8″

WINCHESTER FMC – 130 – 1 5/8″

WINCHESTER JHP – 1258 – 2 7/8″

The Lady Smith

Smith & Wesson J-frames are not only naturals for hikers, campers, fisherman, and even as packin’ pistols by rifle hunters, but they are also quite often picked as defensive pistols by women. In fact, Smith & Wesson has gotten quite a bit of mileage out of its Lady Smith program which began in the last century with a .22 designed to be carried by ladies for protection as they rode their bicycles. The story is that this gun was dropped from production when Joseph Wesson discovered it was being carried less by ladies on bicycles and more by ladies of the night.

A few years back the Lady Smith was resurrected as a variation of the Model 36/60 .38 Special and later as a Model 39 9MM variation. The latest Lady Smiths have been excellent sellers and not only to women. Men who wanted a lightweight, smoothed over concealable weapon have also gone to the modern Lady Smith.

To go along with the J-frames, I requested samples of the wares of

Feminine Protection by Sarah. Sarah uses a very catchy name to offer a serious product, namely purses and belt bags that double as holsters. The handbags and J-frame guns are naturals together and both the Patriot and Classic leather bags supplied accept readily accessible J-frame Smith & Wesson revolvers, and still leave room for all the other stuff that women seem to carry in their handbags.

Both bags open on the front edge to allow instant access to the concealed weapon that many women are going to legally as more and more states are providing licensing systems. The closure system consists of both snaps and Velcro, but they do open instantly when the two halves are parted.

Along with the leather bags came two belt bags or fanny packs. I’m not quite sure I’m ready for a fanny pack but I also remember how difficult it was to carry a concealed weapon last summer during our heat wave. Both belt bags supplied easily carry two- or three-inch .38 Special J-frames. I’m sure my wife and daughter will have something to say about whether these test bags are returned or purchased.

J-Frames and Concealed Carry

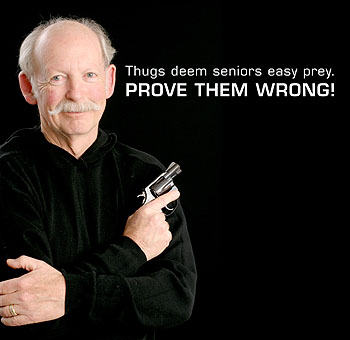

In recent years, semi-automatics have stolen the limelight from S&W J-frame revolvers. People often say that semi-automatics are fast, sexy, and common. They hold more rounds than a revolver ever could. Revolvers are old school, clunky, hard to shoot, and slow to reload. However, the J-frame should not be discounted for certain applications, particularly concealed carry.

First, consider a J-frame such as a .38 Special for concealed carry. The gun is small, light, and easy to stow in a waistband, ankle holster, pocket, purse, or bag. Accidental discharge is unheard of in a concealed carry scenario. Cops have an affinity for the revolver when it comes to deep cover since it’s harder to spot than a semi-auto. The bad guys will be used to checking for a Glock or 9mm. Likewise, the J-frame is ideal for civilians carrying on the down-low.

Some people scoff at the thought of carrying a revolver. They may be old school but still offer the best reliability in a handgun. Revolvers seldom jam. If they do, it’s because the shooter has chosen the wrong, or poorly made, ammunition. Revolvers can indeed be harder to fire because of the double-action trigger. Range practice takes care of that unless you have insufficient grip strength to shoot. J-frames are easier to shoot than K-frame revolvers because of a light recoil. This makes them easy to use for beginners and novices.

A short sight radius gives shooters the impression that snubbies are only worthwhile in close proximity. Not true. Although the accuracy is best at 20-25 feet, an article by a retired detective claims he could easily hit his target up to 25 yards. In a self-defense situation, 25 yards is more than sufficient. You don’t even need to pull your gun if the perp is that far away.

The revolver holds less ammo than a semi-auto magazine but considering that the average self-defense scenario requires three shots or less, you should be okay.

Top J-Frame Revolvers for Concealed Carry

Despite popular opinion, not all snub nose revolvers are the same. Here are my top picks for the top J-frames for concealed carry:

Colt Cobra

The Colt Cobra reared its lethal head at the 2019 SHOT Show. This snubby holds six rounds of ammo, has a 2-inch barrel with stainless steel finish, and a fiber optic, high-visibility front sight. The Hogue Overmolded grips helps to cut down on recoil when using +P loads.

Ruger SP 101

The Ruger SP 101 is on the large side for a J-frame but still worth mentioning. This .357 Magnum has a 2.25-inch barrel and a comfortable grip for those that want extra power over a .38 Special.

Ruger LCR

The Ruger LCR is a lightweight handgun that is sleek, stylish, and affordable. The DAO trigger has a predictable, smooth pull. The LCR is available in many styles and offers choices in .22 LR, .22 WMR, .357 Magnum, .327 Federal Magnum.38 Special, and 9mm. Users can opt for 5, 6, or 8 round capacity.

S&W Bodyguard

S&W Bodyguard is the top choice among law enforcement for backup. The semi-polymer frame makes this model a true modern revolver. It’s available with a built-in integral defensive laser for shooting in low light or awkward shooting positions.

S&W 638

The S&W 638 is the original Bodyguard revolver. It’s not easy to find but worth the hunt. It has a shrouded hammer with a thumb tab that allows you to cock the hammer into single-action mode. It’s a great benefit to have although decocking a gun isn’t something for everyone. Still, it’s easy to conceal.

Final Thoughts

After thirty-five plus years of shooting N- and K-frame revolvers, it is quite enjoyable to add J-frames to my shooting battery. The .38 Special three-inch Trail Masterpiece and the four-inch .22 WMR Kit Gun are destined to experience a lot of use in the future and my wife already has her eye on the .32 Centennial. Oh, well we can get ahead next month.

Article used by permission of the author

http://www.sixguns.com/range/jframes.htm

#1 The Galco Pocket Holster

#1 The Galco Pocket Holster #2 The Galco Concealable

#2 The Galco Concealable

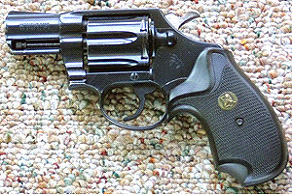

Those many years ago, the snubby I carried was a Smith & Wesson Chief’s Special as shown left. The little gun was one of my favorites for off-duty carry and I was careful to always carry a speedloader with an extra five rounds. I had many an “old timer” tell me that I’d never need more than five rounds – especially off-duty – but I just felt like I needed more. Thankfully I never did need that off-duty gun. On duty the gun sometimes road around in an ankle holster. On at least one occasion I had brain-farted and left my duty weapon in my locker – and when I realized that (out on the street) I reached down to grab the snubby and put it in my waistband. Hey… what can I say? I was all of about 22 years old at the time. We all have those moments.

Those many years ago, the snubby I carried was a Smith & Wesson Chief’s Special as shown left. The little gun was one of my favorites for off-duty carry and I was careful to always carry a speedloader with an extra five rounds. I had many an “old timer” tell me that I’d never need more than five rounds – especially off-duty – but I just felt like I needed more. Thankfully I never did need that off-duty gun. On duty the gun sometimes road around in an ankle holster. On at least one occasion I had brain-farted and left my duty weapon in my locker – and when I realized that (out on the street) I reached down to grab the snubby and put it in my waistband. Hey… what can I say? I was all of about 22 years old at the time. We all have those moments. The other popular snubby at the time was the Colt Detective Special. One thing that I was taught in the academy was that the cylinder on all Smith & Wesson revolvers turned counter-clockwise while the cylinder on Colts turned clockwise. Colt starts with “C” just like clockwise. Of course, so does “counter” but no one ever said that to me so it never clicked. Colts turned clockwise. The Detective Special was impossible to find in stainless steel though and I just knew that any gun that was going to spend time in my ankle holster or pressed up against the skin would rust if it wasn’t stainless. A blued gun just wasn’t going to last. Still, there were folks – experienced cops – who swore by the Colt and cursed the Smith & Wesson. Other knowledgeable shooters I’ve met since then swear by the Smith & Wessons – two of them in fact: one in each pocket of an overcoat. That particular gentleman carries matched Model 66s – stainless steel

The other popular snubby at the time was the Colt Detective Special. One thing that I was taught in the academy was that the cylinder on all Smith & Wesson revolvers turned counter-clockwise while the cylinder on Colts turned clockwise. Colt starts with “C” just like clockwise. Of course, so does “counter” but no one ever said that to me so it never clicked. Colts turned clockwise. The Detective Special was impossible to find in stainless steel though and I just knew that any gun that was going to spend time in my ankle holster or pressed up against the skin would rust if it wasn’t stainless. A blued gun just wasn’t going to last. Still, there were folks – experienced cops – who swore by the Colt and cursed the Smith & Wesson. Other knowledgeable shooters I’ve met since then swear by the Smith & Wessons – two of them in fact: one in each pocket of an overcoat. That particular gentleman carries matched Model 66s – stainless steel  Then, a number of years back, Ruger came out with a snubby that was quite comfortable, offered

Then, a number of years back, Ruger came out with a snubby that was quite comfortable, offered

By Gabe Suarez

By Gabe Suarez

By Ronald S. Markowitz

By Ronald S. Markowitz

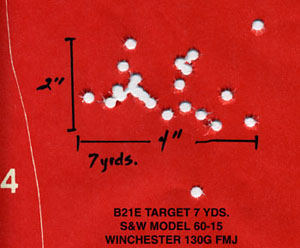

The 3 Model 60 has real sights which are adjustable, the ribbed top rail between the sights, the tapped and screwed-in black rear sight and rail along the top of the frame, and all surfaces are serrated to cut the glare. The front sight leaf is black and is pinned to the barrel. I can actually see these sights. The frame notch sights on the classic snubby really aren’t much use to me, although I have proven that I can use them if I really slow down and get my glaring blurs lined up right. The 3 barrel of the Model 60-15 allows the gun to have a 5 sight radius.

The 3 Model 60 has real sights which are adjustable, the ribbed top rail between the sights, the tapped and screwed-in black rear sight and rail along the top of the frame, and all surfaces are serrated to cut the glare. The front sight leaf is black and is pinned to the barrel. I can actually see these sights. The frame notch sights on the classic snubby really aren’t much use to me, although I have proven that I can use them if I really slow down and get my glaring blurs lined up right. The 3 barrel of the Model 60-15 allows the gun to have a 5 sight radius. The 3 barrel and longer grip gives you a gun that performs better than the classic snubby. It has a better sight radius, better muzzle velocity, more reliable spent case ejection, and less punishment to your hands. For these benefits, you lose pocket carry. The 60-15 doesn’t disappear into a pocket like the classic snubby. I would imagine that it would be awkward in a jacket pocket as well.

The 3 barrel and longer grip gives you a gun that performs better than the classic snubby. It has a better sight radius, better muzzle velocity, more reliable spent case ejection, and less punishment to your hands. For these benefits, you lose pocket carry. The 60-15 doesn’t disappear into a pocket like the classic snubby. I would imagine that it would be awkward in a jacket pocket as well. Aesthetics and Intangibles

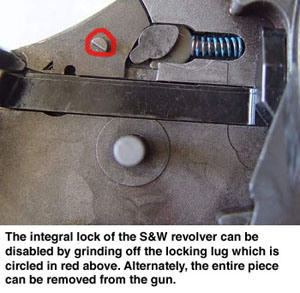

Aesthetics and Intangibles These guns still evoke the cowboy times. The cowboys carried six-shooters but often left the sixth chamber empty so they could put the hammer down without the fear of accidentally setting off a round. So why not build a five-round cylinder with a safe ignition system which would allow the gun to be slim and easier to conceal and carry? Its .357 Magnum chambering reflects the advances in ballistics of the 1930’s. The Model 60, being the first stainless steel revolver, carries the metallurgical advances of the last half of the Twentieth Century. With its key-operated safety lock, it carries the mark of the gun control battles of the late 90’s. Lots of history in these little guns.

These guns still evoke the cowboy times. The cowboys carried six-shooters but often left the sixth chamber empty so they could put the hammer down without the fear of accidentally setting off a round. So why not build a five-round cylinder with a safe ignition system which would allow the gun to be slim and easier to conceal and carry? Its .357 Magnum chambering reflects the advances in ballistics of the 1930’s. The Model 60, being the first stainless steel revolver, carries the metallurgical advances of the last half of the Twentieth Century. With its key-operated safety lock, it carries the mark of the gun control battles of the late 90’s. Lots of history in these little guns. Interesting Lawyer-Friendly Stuff

Interesting Lawyer-Friendly Stuff There has been some discussion of these safety locks engaging when they shouldn’t. In the January 2005 issue of American Handgunner, Massad Ayoob published an article about

There has been some discussion of these safety locks engaging when they shouldn’t. In the January 2005 issue of American Handgunner, Massad Ayoob published an article about  Range Report

Range Report With a 5-shot J-frame, the issue of firepower always comes up, and if you want to carry these guns,

With a 5-shot J-frame, the issue of firepower always comes up, and if you want to carry these guns,

Smith & Wesson Models 40, 42, 640, 940, 442, 642, 340Sc, 342Ti and 340PD

Smith & Wesson Models 40, 42, 640, 940, 442, 642, 340Sc, 342Ti and 340PD

By Syd

By Syd In 1942 Smith & Wesson built a few Victory Model Military & Police revolvers with 2″ barrels. In 1946, they began commercial production of the

In 1942 Smith & Wesson built a few Victory Model Military & Police revolvers with 2″ barrels. In 1946, they began commercial production of the  The Rationale of the Snubnose

The Rationale of the Snubnose The Art of Compromise

The Art of Compromise

Conceal-ability

Conceal-ability A Gun That Is Always With You

A Gun That Is Always With You